Dandyism in Dance

Celebrating Black History Month

WRITTEN BY AYO JANEEN JACKSON

WEEK 3

The Harlem Renaissance

The Joyce Theater celebrates Black History Month by uncovering hidden narratives that set the stage for shows we enjoy today, from Broadway to The Joyce Theater. This initiative will investigate how Dandyism appears in dance. This is the second of four blog posts that will highlight how Black men have shaped American forms of dance and entertainment.

We will explore how Dandyism shows up within several different contexts: Minstrelsy & Vaudeville, The Harlem Renaissance, and Ballet & Contemporary Dance forms.

The New Negro

For Week 3 of Dandyism in Dance, we’ll spotlight cultural producer Leonard Harper, an entertainer whose flamboyant style helped define the Harlem Renaissance and the Cotton Club aesthetic. As we explore Dandyism in 20th century dance, it’s important to look at the historical backdrop that shaped Harlem in the 1920s. During this period The Great Migration brought Southern traditions, food, and culture to northern cities. Millions of Black Americans went to places like Detroit, Philadelphia, and, most famously, Harlem. In Harlem, entertainment took on a new life—style and performance were not just on stage; they were in the streets. Southerners stitched together language, clothing, and performance, transforming themselves into the high-falutin big shots that New York expected. Harlem was having a Renaissance.

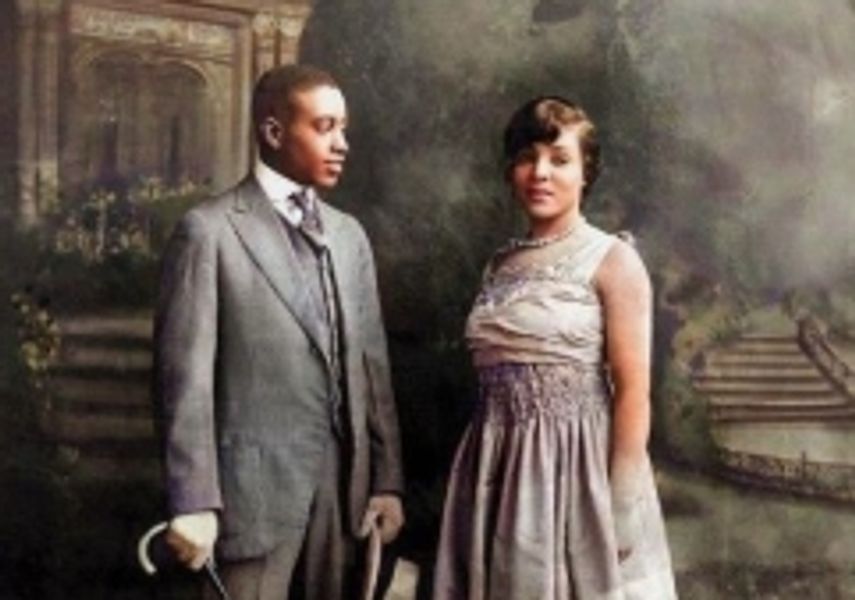

This era saw an explosion of Black artistic and intellectual expression, and was famously articulated by writer and philosopher Alain Locke in The New Negro. Locke described this period as a cultural awakening in which Black artists, writers, and performers redefined their identities, shedding the imposed narratives of the past. The Harlem Renaissance was a defining moment for Black Americans. Often called a mecca, Harlem, was seen as a safe space where Black people could finally lay claim to the American Dream. Much like George Walker before him, Leonard Harper began his career in medicine shows as a child, learning the art of spectacle. Born in Alabama in 1899, Harper migrated north, first to Chicago and then to New York City. He got his start in Chicago, performing and choreographing for the Blanks Sisters, later marrying one of them, Osceola, in 1923.

Harper excelled as a producer, stager, and choreographer, bridging the gap between the nightclub stage and the silver screen. He worked in Harlem clubs featuring Duke Ellington’s band and eventually choreographed for Oscar Micheaux’s The Exile. His first big break came with Plantation Days, a revue that set the tone for his signature nightclub revues–always bold, lavish, and attention-grabbing—a style he honed during his early days in medicine shows. His productions became known for their flair, spectacle, and, of course, a bevy of beautiful dancing girls.

The Cotton Club, once a supper club owned by boxer Jack Johnson and called the Club Deluxe, was the epitome of luxury even though the club remained racially segregated. Harper played a pivotal role in shaping the Cotton Club’s identity, serving as the premiere producer in its transition from the Deluxe Club to the legendary venue in 1923. “His wonderful artistry helped the uptown Cotton Club to become internationally known.” The Cotton Club featured and made famous so many Black entertainers that we know and love today: Cab Calloway, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Ethel Waters. It also featured The Cotton Club Girls, who were chosen for their fair skin and slender frames. Some notable dancers from the club included, Jeanie Martini, Gertrude Williams, Ruth Dash, Mamie Jeffries, Delores Myers, and Julia Noisette.

Leonard Harper was known for staging large ensemble numbers with crisp, synchronized formations—a technique that influenced later Broadway choreographers. Harper’s choreography reflected the social and cultural shifts of the Harlem Renaissance. His revues were not just about entertainment; they showcased Black excellence, elevating vernacular styles like the Charleston and tap dance. His choreography blended structured routines of formal choreography with the wild improvisational spirit of vernacular dance. This juxtaposition is captured in the film The Exile, where we see a large ensemble of dancers executing high kicks, rapid turns, and complex rhythmic sequences, all while maintaining an effortless showmanship. This effortlessness is a key characteristic of dandyism.

Harper’s influence extended beyond the stage—he “became one of the guiding lights of New York nightlife in the ‘20s and ‘30s.” His work contributed to the broader image of the Harlem Renaissance as a time where Black artistry flourished. Harper was also a sought-after dance teacher. His midtown studio became a training ground where Black instructors taught white performers, including Fred Astaire and the Marx Brothers, the rhythms and movements of Black dance.

Harper’s artistry was not just in his choreography—it was in his ability to navigate high society, and redefine what Black performance could be. Dandyism, at its core, is more than fashion; it is a deliberate performance of identity. Harper embodied this through his work, presenting Black entertainers as sophisticated, stylish, and worthy of the spotlight.

A Variety review from the time reflects the racial dissonance that Monica Miller explores in Slaves to Fashion: the idea that Black people inherently embody dandyism because, in a world that expects them to be subservient, dressing up itself becomes a performance. The review reads:

“A quartet hacked away in dress suits when it should have been plantation jumpers. Gowns when they should have been fancifully dressed as pickaninnies, zulus, cannibals, and cotton pickaninnies.”

This expectation, that Black performers should adhere to stereotypes rather than sophistication, underscores how radical Harper’s vision was. By insisting on glamour and elegance he redefined the image of Black performance. Leonard Harper embodied the essence of the Black dandy—elegant and confident—and his work reflected the ambition of the Harlem Renaissance: unapologetically Black and revolutionary in its essence.