Dandyism in Dance

Celebrating Black History Month

WRITTEN BY AYO JANEEN JACKSON

WEEK 4

Pomp and Circumstance

The Joyce Theater celebrates Black History Month by uncovering hidden narratives that set the stage for shows we enjoy today, from Broadway to The Joyce Theater. This initiative will investigate how Dandyism appears in dance. This is the second of four blog posts that will highlight how Black men have shaped American forms of dance and entertainment.

We will explore how Dandyism shows up within several different contexts: Minstrelsy & Vaudeville, The Harlem Renaissance, and Ballet & Contemporary Dance forms.

As we round out the final week of this series on Dandyism in Dance, I want to reflect on how much this project has deepened my understanding of Black Dance in America. It has revealed the ways in which resistance is embedded in the elaborate costumes and decorations that accompany official ceremonies. The display of luxury within these dances and dancers speaks to a broader struggle for equality.

Across each of these blog posts, I have witnessed how Black people have used dance as a vehicle toward liberation for centuries. The steadfast resistance by repurposing the “leftovers,” performing in segregated clubs, or adapting traditions to fit their own needs—has been a strategic way of self-fashioning, of making the material fit. This week, we examine two striking examples of that flair: the illustrious Dance Theater of Harlem’s Firebird and the historically Black college marching band tradition, both of which embody the spirit of dandyism.

“Black dandies may seem to mimic European dress styles in an effort to accrue the power associated with whiteness. Such repetition, however is never a strict copy of the original style, but a black interpretation of it designed to offer the black performer a greater sense of mobility and creativity within the expressive form”

-Monica Miller, Slaves to Fashion

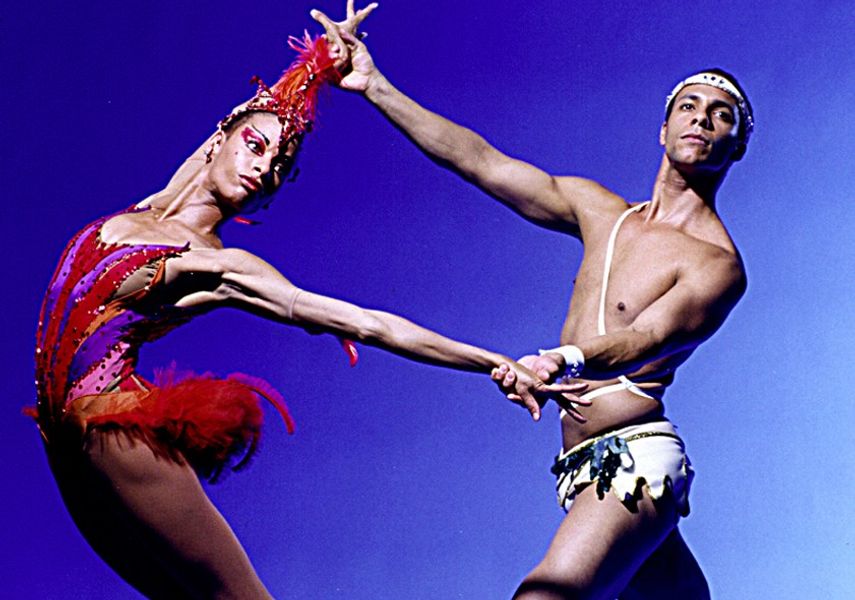

FIREBIRD and The Dance Theater of Harlem

Arthur Mitchell became the first Black ballet dancer with New York City Ballet (NYCB) in 1955. The following year, he became a principal dancer, taking on leading roles. In 1969, in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., he founded a school and ultimately —Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH)—a pioneer in the dance world, integrating stages and spreading the art of ballet through massive outreach programs at home and abroad. In 1963, Arthur Mitchell danced in the original cast of Arcade, choreographed by John Taras for NYCB. Years later, Taras staged Firebird for Dance Theatre of Harlem, wanting to remove the ballet from its Russian origins. In an interview with David Sears, Taras explained that he had never liked any of the Firebird versions he had seen, though he found the ballet itself beautiful. His 1982 production, which premiered on May 5th at The Kennedy Center, reimagined the story in a mystical Caribbean forest. As noted by Sears, this Firebird was more defiant than the ABT version.

“She is a supreme being, you know. She has never been questioned; there’s never been any possibility of capture or anything like that. When the boy appears, she has to resist terrifically.”—John Taras

In speaking about Dance Theater of Harlem dancers John says: “They can do it better than anyone…They believe in everything that they do and that’s hard to get out of Modern dancers these days. You know, they all have opinions about what they should be dancing. And what’s rather nice about these dancers is that they want to do everything. You have to be convincing if you’re going to do something like Firebird.”

The costumes and set were designed by the noble multidisciplinary artist Geoffrey Holder—a dancer, actor, choreographer, designer, and dandy in his own right. Holder’s vision was one of enchantment; he crafted costumes that adorned Black ballet dancers like second skin, giving the feeling as if they were painted on and embellished with jewelry. The Firebird’s red-feathered costume accentuated every movement, a blend of grace and majesty. The set, constructed in London, was later shipped to the U.S. Taras selected Holder for his unmatched flair, explaining:

“...he really has a marvelous flair for things. And I thought, especially since I wanted to get it out of Russia, I thought he’d be the ideal person. He understands so easily what one wants. He also knows how to dress those Black bodies. That is what’s very important cus I don’t want them to be imitating white people. I want them to be what they are.”

It should be noted that the interviewer and several other critics complained about the seeming difficulty of wearing some of the costumes because of the long sleeves and scarves. John responds

“All those skirts are very useful….There is a point where it should be very elaborate and very dressed and pompous and dignified. It’s mostly procession at the end. I think that he will do particularly well.”

The result was a Firebird that was distinctly Black—reinterpreted and redressed with a sense of grandeur that was truly dandy.

"Firebird" will be returning to Dance Theater Harlem in 2026

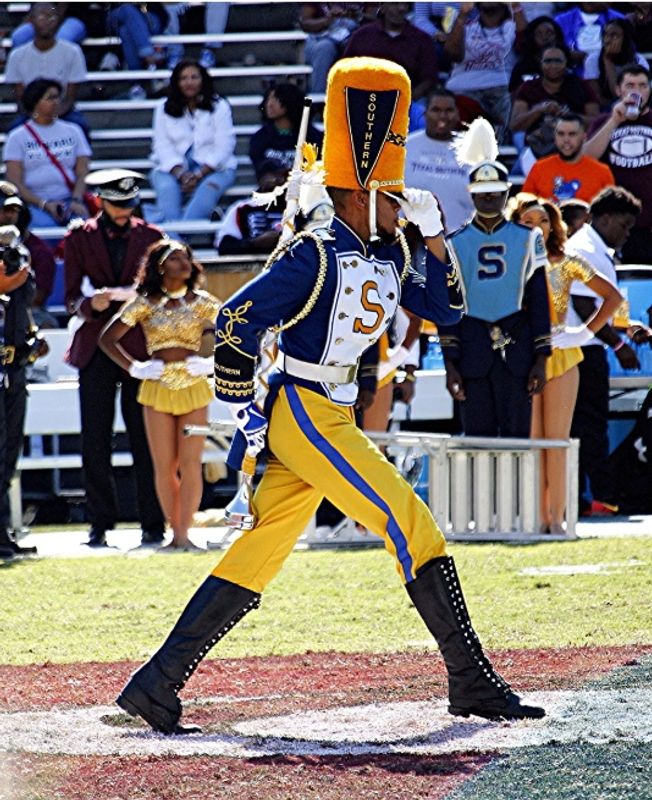

The Black Marching Band Tradition

Black marching bands have their roots in military tradition, with Black musicians serving in Colonial-era militias. During the Civil War, all-Black regiments had their own instruments and bands, many of which continued after the war. The tradition resurfaced during World War I, with Black military bands producing musicians who went on to lead music departments at budding Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

Many believe that Black marching bands draw inspiration from West African Yoruba funeral processions, where musicians play instruments and dance, as well as from Black drill sergeants who infused syncopation into their footwork. By the 1960s, HBCU marching bands had transformed the rigid military aesthetic, incorporating the rhythms and movements of Black music and dance. The style was revolutionized at Florida A&M University (FAMU), under the leadership of Dr. William P. Foster.

While working at Tuskegee Institute, Dr William P. Foster was approached by Florida A&M’s president Dr. Gray, to develop a milestone program for their marching band. Foster began teaching at FAMU in 1946. He went on to lead the “Marching 100.” His innovative approach developed what we know the Black college marching bands to be today.

Dr. Foster’s three-pronged approach of the dance, the music, and the thematic development established a form that has focused the style of HBCU halftime shows. Dr. Foster spoke of how he took the basic movements of drill techniques and exaggerated them. Large sweeping movements were more effective than small detailed ones. Their shows were designed to be precise. The instrument had to correlate with a knee lift. He noted the musical selections and arrangements were very important in gaining sympathy from the audience; basically he played what the audience was familiar with--something they could dance to. And finally, the thematic development was something that brought the whole performance together; he related it to producing a TV show.

“It was to the tune of ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band.’ We were just doing steps and high-knee lifts, and people thought that was the greatest thing on earth. Later, I had a physical education teacher, Beverly Barber, help with the choreography, putting the steps to music.”

-Dr. William P. Foster

The marching bands of today encapsulate Dr. Foster’s vision. The drum majors are a central act in the marching band show. They stride across the field directing the band where to march, what to play, and when to keep time. Though each one has their own style, they usually are dressed in a tall hat (made of leather and ear fur) often accompanied by a cape. Their dance style consists of an affected form of marching, almost prancing. The most awe-inspiring move is the backward arch, where they touch the ground with the top of their hat in a dramatic display of flexibility and control. As the music plays familiar tunes, the brass instruments' hollow sound transports the audience into a chorus of swaying onlookers.

This style of dance or movement is quintessentially dandy. It has taken the ROTC marching form and worn it like a new suit draped on a body, having had years of restraint, became a new form of liberation.

A Legacy of Black Dandyism

In this post, we explored two American performance traditions—ballet and the marching band—reimagined on and for the Black body. As we close out Black History Month, we want to honor the legacy of Master Juba, George Walker, Leonard Harper, Arthur Mitchell, Geoffrey Holder, and Dr. William P. Foster. These men embodied the essence of the Black Dandy—not simply adopting the structures given to them but refashioning them into something extraordinary.

By redressing themselves—both literally and figuratively—they carved out new spaces for Black excellence. Their contributions remind us that dandyism is more than aesthetic; it is a declaration of presence, resistance, and transformation from The Cakewalk to Capes.

Happy Black History Month! Thank you for reading!