Dandyism in Dance

Celebrating Black History Month

WRITTEN BY AYO JANEEN JACKSON

WEEK 2

Minstrelsy & Vaudeville

The Joyce Theater celebrates Black History Month by uncovering hidden narratives that set the stage for shows we enjoy today, from Broadway to The Joyce Theater. This initiative will investigate how Dandyism appears in dance. This is the second of four blog posts that will highlight how Black men have shaped American forms of dance and entertainment.

We will explore how Dandyism shows up within several different contexts: Minstrelsy & Vaudeville, The Harlem Renaissance, and Ballet & Contemporary Dance forms.

Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but can it also function as a tool of resistance and transcendence? This post examines how African-American performers navigated the entertainment world despite being racially mocked. We will explore mockery vs imitation in performance by using as our subjects two legendary dancers, Master Juba, and George Walker, as well as a dance, the Cakewalk. Minstrelsy was meant to mock, but who was imitating whom?

While many artists of color donned blackface for employment opportunities, the psychological toll was undeniable. Historian Eric Lott identified this strange predicament - a black man imitating a white man imitating a black man.

Master Juba and George Walker found themselves outside of this irony, wielding imitation as a tool for self-determination. Black Americans have long used mimicry as both a form of resistance and a survival tactic. These men’s stories and the widespread popularity of the Cakewalk demonstrate how Black people gained agency by imitating the white upper class.

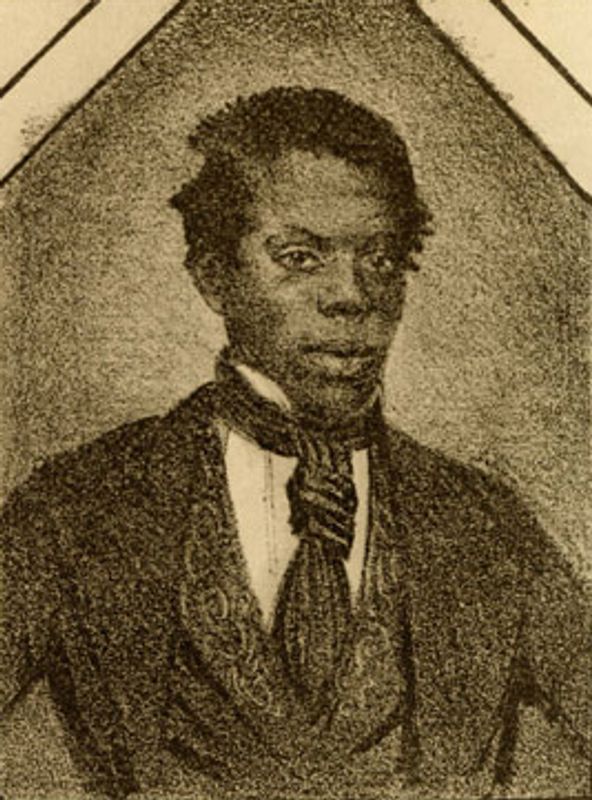

Master Juba, also known as William Henry Lane, was a pre-Civil War Black hero, who used his virtuosity in dance as a vehicle towards liberation. Born in 1825, Master Juba is considered the creator of tap dance. He rose to fame from the squalor of Little Five Points, a neighborhood in southern Manhattan where poor Irish immigrants and freed Black people intermingled. One popular dance hall, Almack’s, located at 67 Orange Street was run by a Black man named Pete Williams; it was there Master Juba showcased his talents.

At a time when minstrelsy was at its height due to an increase of white male spectators who escaped to the theater amid a financial recession, Master Juba defied what a Black entertainer was permitted to perform. One of his signature acts was to imitate the finest white male dancers of the time, such as John Diamond. His performance was an elaborate display proving his mastery of his competitors' styles and the superiority of his unique dance moves. Charles Dickens was in complete awe of seeing Master Juba perform at Almack’s as he describes in his travelogue, American Notes:

"Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man's fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs—all sorts of legs and no legs—what is this to him?”

This review by Charles Dickens made its way to England and Master Juba’s reputation preceded him. He found himself there toward the end of his life as the only Black man to perform with an all-white minstrel group, The Ethiopian Serenaders.

A fine example of dandyism in dance, Master Juba’s ability to mix European and American dance styles was a statement of self-ornamentation, clothing himself in social value and upward mobility.

Where Master Juba used imitation to assert artistic superiority, George Walker transformed the image of Black masculinity in entertainment. Born in 1872 in Lawrence, Kansas, George “Nash” Walker began as a young dancer in medicine shows and went on to become a dandy in the original sense. He used clothing to assert his value in show business as well as the segregated world at large.

In 1893, he met his longtime performing partner Bert Williams in California. While they billed themselves as “The Two Real Coons” to differentiate themselves from the white performers, George did not perform in blackface. He left the comedy of minstrelsy’s bulging eyes and enlarged colorless lips to Bert Williams, known at that time as one of the funniest men alive. George was carefully crafting an image of the Black man as articulate, formidable, and wealthy.

In 1907, the Toledo Courier interviewed George Walker on his stance:

“[George Walker] explained his reasons for extravagant and costly stage costumes and good, expensive street clothes. Dress is George Walker’s stock in trade. It is a part of his method of making business. He believes in the modern American idea that the most successful businessmen in the county are the men who know how to advertise their business to advantage, and he contends that clothes help to advertise his and his partner’s theatrical business…

[Recalling an incident where a white man questioned] “May I ask why you wear such flashy clothes and that large diamond ring?” And I told him that in many cases white people would not believe I was George Walker if I did not wear them. The general public expects to see me as a flashy sort of darky and I do not disappoint them as far as appearance goes.”

Walker wasn’t just a performer, he was a visionary producer. He and Williams were credited as the first Black recording artists. The group Williams & Walker, along with his wife the incomparable, Aida Overton Walker, produced the first Black musical-comedy on Broadway, In Dahomey: A Negro Musical Comedy (1903). Between 1902 and 1904, he and Bert Williams made approximately $130,000 yearly, which is $3.2 million today. Walker was not only exceedingly rich, but he leveraged his achievements to create avenues for other Black performers. Along with Williams, Walker established The Frogs, a professional network for Black theater artists.

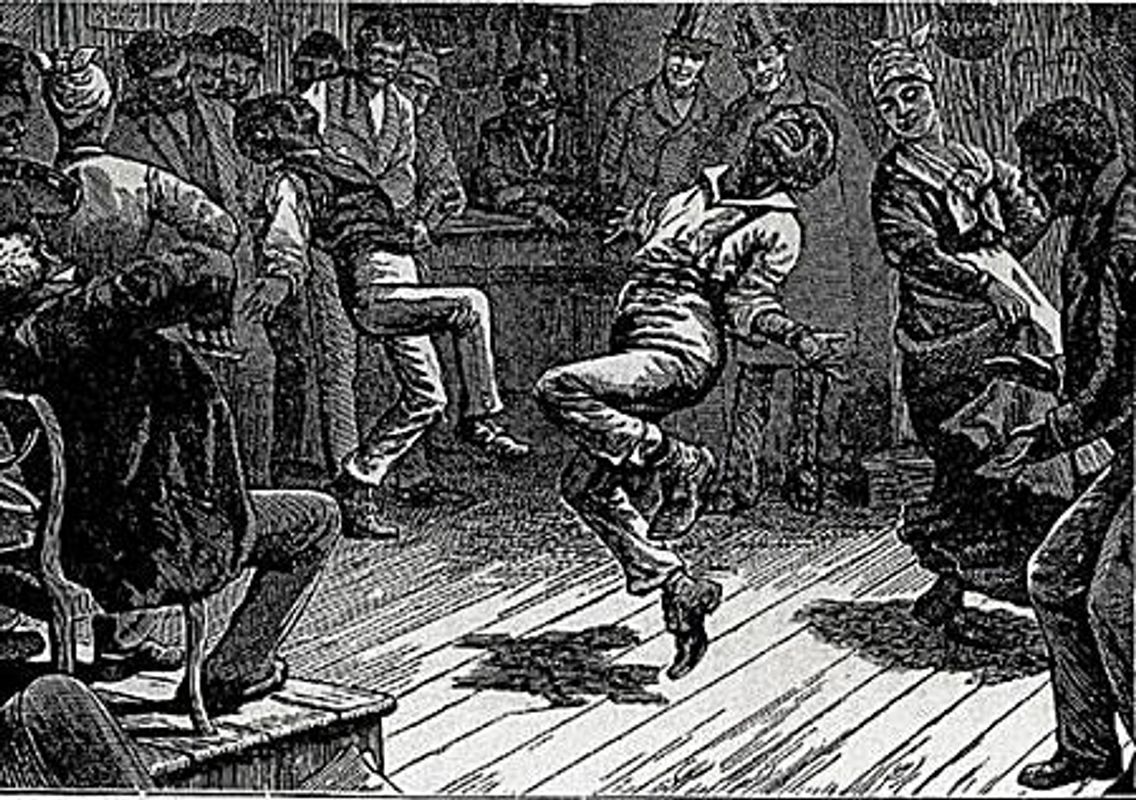

Where George Walker and Master Juba embodied dandyism in dance, the Cakewalk furthered the spirit of dandyism by employing satire as a means of ascending the social hierarchy. What began as a 19th-century plantation dance evolved into a competitive event with a cake as the reward.

At its core, the Cakewalk is dandyism in motion—the embodiment of luxury and refinement. Black dancers remixed the aristocratic dance moves of plantation owners, most likely European waltzes.

The Cakewalk became famous in Vaudevillian shows, spreading its popularity. The dance is all about light, springy steps—once you’ve got the basics down, you can start adding flair. While some moves can get pretty intricate, cakewalking is more about performance than technique because the cakewalk is an act of celebration. The couples competing would march around inserting improvisational gestures to accentuate their presence on the dance floor.

The Cakewalk wasn’t just a dance, it was a performance of self-actualization and ascendence. Dandyism in dance can then be defined as imitating social elegance and style through virtuosity, poise and grace, and clothing. The mockery of minstrelsy didn’t offer an opportunity for transcendence. While the white actors who donned blackface sought to distort and oppress Black identity, they could never quite capture the wit and transformative power of imitation within Black performance.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.