Juel D. Lane and the Legacy of Ernie Barnes

Choreographer Juel D. Lane pays homage to his childhood inspiration, painter Ernie Barnes, with "Incense Burning on a Saturday Morning: The Maestro."

For its 2025 engagement, BODYTRAFFIC brings “This Reminds Me of You” to The Joyce, a program that dives into the power of memory and embraces how certain pieces of art can evoke deep feelings of nostalgia. For one of the three choreographers, Juel D. Lane, this means revisiting an early childhood inspiration of his: the prolific African American painter Ernie Barnes. Lane’s Incense Burning on a Saturday Morning: The Maestro pays tribute to Barnes’ legacy, emphasizes resilience, and serves as a poignant reminder of our shared humanity.

But, who is Ernie Barnes?

.jpeg)

Ernie Barnes’ story exemplifies the power of artistic expression. Growing up in segregated North Carolina, Barnes’ only exposure to the fine arts came when his mother brought home classical music records and books showcasing the work of groundbreaking artists, such as Michelangelo. His mother, who worked as a housekeeper for the Durham attorney, Frank L. Fuller, Jr., sought to broaden her children’s horizons and even encouraged them to draw from their imagination rather than using coloring books. Bullied for being chubby and uncoordinated in school, Barnes looked to art and football as an escape. After receiving 26 athletic scholarship offers, Barnes enrolled in North Carolina College at Durham (now North Carolina Central University), majoring in art. On a freshman year field trip to the North Carolina Museum of Art, Barnes sought works by artists that looked like him. However, when asking where the Black artists were being showcased, the museum employee responded that there were no Black artists on display because Black people “don’t express themselves that way.”

In 1960, Barnes left school to go pro, playing for a succession of American Football League (AFL) teams, including the Chargers, the Broncos, and the New York Titans, while continuing to sharpen his artistic skills. He’d often sketch his fellow players, leading to his nickname “Big Rembrandt.” After retiring in 1965, Barnes committed to painting and was named the AFL’s official artist shortly after his final game. After seeing Barnes’ work, New York Jets owner Sonny Werblin arranged a showing for critics at a New York gallery and paid the artist $14,500 (more money than he made his last season playing football) to paint 30 paintings over the span of six months. From the buzz of this exhibition, Barnes began receiving larger commissions, including celebrities like Harry Belafonte, Flip Wilson, and Charlton Heston.

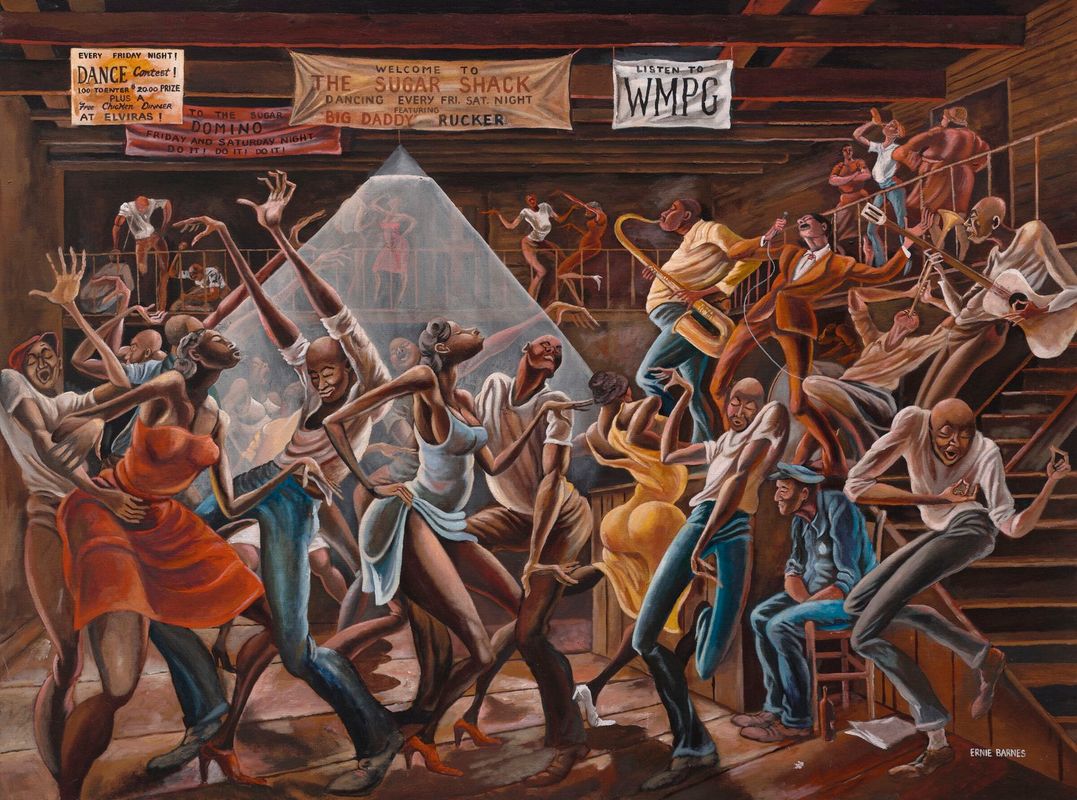

In the mid-1970s, Barnes’ art became inextricably linked with Black pop culture history when a television producer, Norman Lear, commissioned him to work on Good Times, the groundbreaking sitcom marking the first appearance of a two-parent African American family. JJ Evans, the family’s wisecracking oldest son, was an aspiring painter whose “paintings” were actually created by Ernie Barnes. Barnes’ 1976 painting, “The Sugar Shack,” was featured in the show’s closing credits, forever tying his art with the legendary program.

Barnes’ background as a professional athlete gave him a deep knowledge of the body and how it reacts to movement, thus allowing him to craft an unmistakable style that set him apart. His work is known for elongated limbs and exaggerated poses, making it appear as though his subjects almost jump off of the canvas. Vivid color and sweeping lines bring an electricity to his work that evoke a rich emotionality from his subjects. These subjects demonstrated Barnes’ commitment to exalting everyday life, from athletes to dancers in a juke joint to a young boy walking down the street. In capturing these snapshots of life, Barnes strove to convey the Black experience as more than hardship.

Ernie Barnes’ art has inspired people across generations, including choreographer Juel D. Lane. As BODYTRAFFIC brings his testament to Barnes’ legacy, Incense Burning on a Saturday Morning: The Maestro, to The Joyce, Lane reflects on the impact Barnes has on his artistry and how it feels to be paying homage to the icon through dance.

During an interview with the company, you said that you first discovered Ernie Barnes' work through the character JJ on Good Times and thought, "Wow. That looks like me." Why do you think his work was so impactful for you then?

In my household, Saturday was our day to clean or get the house in order—a time to relax and take a break from the Monday–Friday hustle. My parents introduced my sister and me to music; Soul Train was on, and sometimes we’d watch reruns of Good Times. The opening and closing credits featured Ernie Barnes’ “Sugar Shack” painting, which always felt like a bold affirmation: “Whatever is going on in life, there’s still movement”—movement that releases us and prepares us for the next day. My mind would wander even further when I saw that same painting on a Marvin Gaye album—I Want You. Then I started to notice it in my friends’ homes when I visited. And every Black household, even before I fully understood that it was an Ernie Barnes work. Seeing that image was a reminder of the necessity of Blackness. It was a badge of honor.

What about Ernie Barnes' artistry resonates with you now?

I love how real and honest his pictures are. It’s like making cabbage: you get the stalk, cut it up, add your smoked turkey necks, let it create a broth that the cabbage can live in, then add your onions, bell peppers, and seasonings, and close the lid. When that aroma hits you, it feels familiar and ancestral. That feeling is hard to take away. It’s like in his painting, “The Graduate,” which depicts a figure walking with a diploma and exudes a sense of pride and accomplishment: holding that diploma and feeling like you just achieved the greatest thing in the world reminds me of getting my diploma in high school and how it was important to add to my legacy or simply finish something. So yes, his work reminds me of home and eating a good plate of soul food.

You first explored Barnes' work through dance in 2018 with your short film The Maestro. What about his work continues to enrapture you through these years?

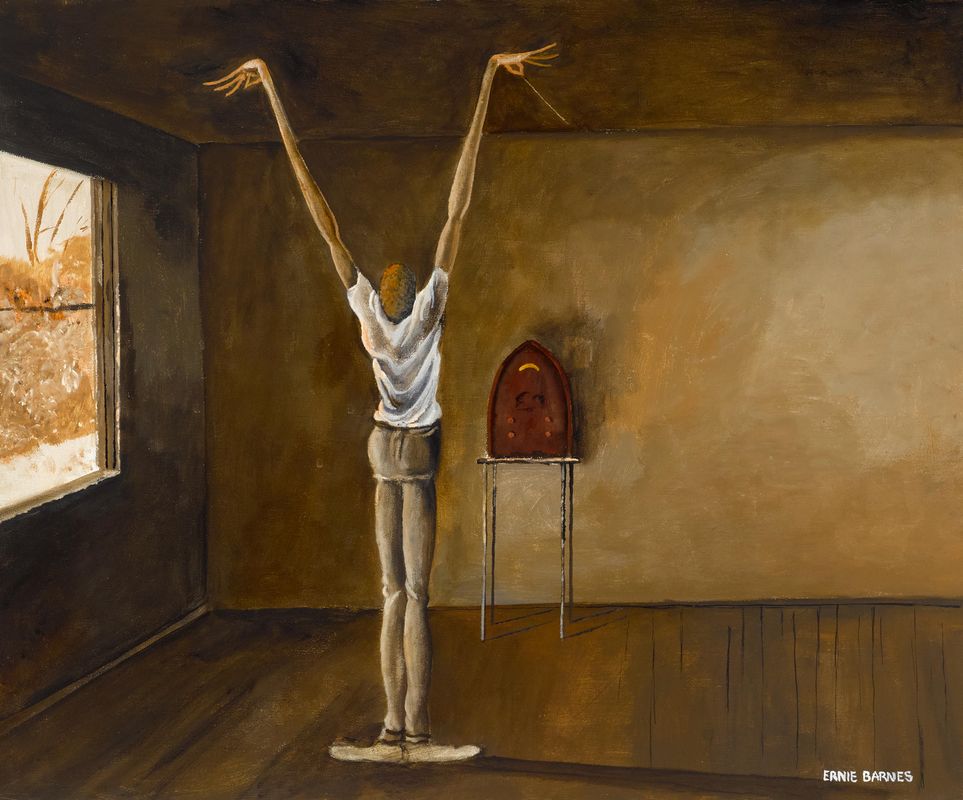

I love how his work makes my imagination spiral into the unthinkable. “The Maestro” is so simple in its structure, yet it allowed me to create my own narrative about what I think it is. In my mind, it’s about being the conductor of your life—getting out there and making things happen. It’s like Ernie purposely created visual affirmations for us to ponder and think big. That's the power of looking at his paintings, they give your imagination time to play.

Barnes' trademark neo-mannerist style with exaggerated forms and elongated proportions evoke the sensation of movement. Can you describe the process of adapting Barnes' unique style of painting movement into the third dimension for this work?

That part was so much fun. I took notes from my high booty, long legs and arms-similar to the way Barnes paints Black people-and went on to play with how much I could reframe a phrase and draw things out with that idea of elongation. Elongation felt like pulling from things that are naturally me to aid in movement exploration, like Atlanta's dance, particularly "YEEK." YEEK dancing has always been rooted in me since I was young, so I wanted to expand on that as I was cooking with the choreography.

To you, why is it important to remember Ernie Barnes' legacy?

It’s important to remember Ernie Barnes because I always feel like he painted things that brought him joy. He painted with a sense of finding richness wherever he went and not allowing people to say he wasn’t worthy of being part of the conversation. It feels like the underdog, but his success was fulfilling his passion. When you transition to the next realm of your life, you want your stories or impact to serve as an ancestral guide that continues to breathe life into someone who wants that light or hope to be inspired. To me, that’s the legacy.

Want to learn more? Check out this mini-doc and dive deeper into the creation process for Incense Burning on a Saturday Morning: The Maestro!